Landscapes for Small Spaces

Katsuhiko Mizuno

book reviews:

· general fiction

· chick lit/romance

· sci-fi/fantasy

· graphic novels

· nonfiction

· audio books

· author interviews

· children's books @

curledupkids.com

· DVD reviews @

curledupdvd.com

newsletter

win books

buy online

links

home

for authors

& publishers

for reviewers

|

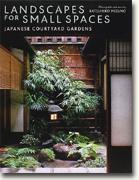

Landscapes for Small Spaces: Japanese Courtyard Gardens Katsuhiko Mizuno John Bester (Translator) Kodansha America Hardcover 120 pages October 2002 |

|

Landscapes for Small Spaces is about indoor gardens of a special type: very small courtyards. There is word for them, tsuboniwa (a word that is prettily rewarded on a Google search). Niwa means garden; tsubo derives from an early measure of distance, roughly ten feet. Although that measure is not a dictat for a tsuboniwa layout, many of the book’s 100 gardens are close to it. Author Katsushiko Mizuma narrows his subject even further by including only tsuboniwas in the city of Kyoto and nearby. Tsuboniwa began very simply, in part a successful adaptation to architectural styles that began in the Heian Period (794–1185), in which closely adjacent buildings were connected by covered corridors. This in turn created small open spaces. Kyoto’s hot summers gave garden designers every reason to come up with layouts that were cooling as well as pleasing. It also made possible a principle feature of the tsuboniwa: the ability to be viewed from many angles and perspectives. Soon perspective became a metaphor for sequestering. Some gardens were designed to be seen from only one location (and in a few cases only through an aperture in a shoji screen). Others were designed to be viewed from two locations (often inducing different impressions). Still others lay in the middle of ambulatories meant to be walked around meditatively, just as medieval and renaissance abbey cloisters were meant to be viewed from the unreeling change of a slow stroll. The effect is like watering one’s own garden by walking its periphery, seeing how the whole can be viewed from a multitude of points of reference which add up not to the whole but to more than the whole. The metaphor is that any one view of a thing is only a tiny fragment of all. It is beyond the all that one must seek, no matter from which point of view one happens to see. Relinquish your point of view and you relinquish yourself; only then will the all, the greater-than-whole, be perceived. The three gardens which open the book are among the earliest to have been created, and common to them is a single message. A tsuboniwa in the ancient Kyoto Imperial Palace consists of a lone wisteria in a rectangle of pea gravel. A small tuft of green moss carpeting beneath wisteria trunk reminds one that nature must be left to nature no matter how managed the surroundings. In the same palace, behind the Emperor’s personal quarters, is a courtyard garden comprising twenty small shrubs, also set in pea gravel, surrounded by ancient wooden walkways with vertical columns of simplicity but horizontal balustrades of structural—though not decorative—complexity. The garden is a reminder of the Emperor’s taut duties of presiding over a busy, layered, court life while presenting a personal demeanor akin to what would be called Olympian detachment in the West. Finally, in the Shinto shrine at Kamigamo, a cluster of miniature bamboo (a special species prized for its smallness) froths skyward, placed off-center in a rectangle of white sand. A few unclipped grass blades remind one that this garden is pretty much left to be what it is, century after century. The commonality to all these is allegoric: isolation in the sea, an island of elegance and balance in a sea of time. There are other harbingers of Japanese taste that were not fully formalized for

centuries. One is the absence of symmetry; another is disinterest in perspective

trickeries whose purpose is to fool the eye. What you see is what you get. There is a number of Zen “dry gardens” (those with the raked stones), and, like a koan, they use the obvious to beg answers to the cryptic and enigmatic. At the Tokaian Temple, a garden of gravel raked into concentric circles around an off-center focal stone—the smallest of seven in the garden—hints at the unfathomability and limitlessness of the cosmos. Yet consider more deeply: the sea of infinity is also the sea of one’s innerness. This is the message intended upon the devotees who periodically re-rake the stones into exactly the same formation they were before as part of their duty of “walking meditation,” a form of vipassana intended to achieve the same transcendence aimed for by the more familiar cross-legged samadhi, or sitting meditation. At the Totekiko Garden in the Ryogen’in Temple the stones are raked into concentric circles around a lesser stone at each end, set amidst a linear row of furrows from end to end. The ripple effect around the focal stones reminds one of the ripples made by a drop of life on the flow of time (represented by the straight furrows). About midday, the sun cuts a narrow blast of light straight through the garden, announcing the obvious to any Buddhist: The light of the Buddha illumines the relation between existence and time. Several images show these gardens in the winter with the snow partly melted and are especially evocative. At the Kyoo Gokokuji temple in the complex of Kanchiin is a “semi” dry garden as perfect as a refined aesthetic can create. An irregular stream of white gravel is embanked by rock groups, ferns, tall grasses, shrubs, and trees. The overall effect is flowing into the sea of time through the world of being. It is one of the most breathtaking tsuboniwa in the book. A tsuboniwa at a Buddhist nunnery is graced by the 400-year-old azalea, whose fallen petals become a carpet confetti of creamy lavender-pink and ecru decaying inevitably into tinges of brown, at once a reminder of the transitoriness of beauty and the cycle of the seasons—life itself—which brings beauty back once again only to pass into decay once again. The more complex gardens at first are more attractive to the eye, perhaps because the purpose of the eye is to embrace all in its myriads of detail.* Then note that the more striking gardens are those with very few elements—the adornment of the least needed—which stops the inner eye in its tracks and asks it to stop looking and start seeing. Send the unnecessary on a vacation the garden says, and refresh your self here. * [Amaze for a moment at the task of the brain as it processes millions of pixels each the size of a retinal receptor cell, at roughly ten times a second, stores them in short-term memory, processes them, informs us of what is moving and what not; and all of this but a tiny fragment of the brain’s job as it then assesses priority, hierarchy, appropriate emotive response, and finally for those with the leisure to contemplate, meaning.] On the opposite end of the scale are gardens, as at the Reikanji and Daishin’in temples (with a 360-year-old azalea!), whose focus is not inanate line and stone refusing the enticements of existence, but lush, dense, flowering trees, each coming into bloom in succession through the warm months. These gardens are the Japanese equivalent of the numinous, a nonphysical presence or spirit of place presiding in a locale—and also regenerative energy, since the designers were so mindful to cycle that they planted not for themselves but for many generations beyond them. There’s a Zen Buddhist phrase, “Water in the bucket, rice in the pail,” which alludes to the desire for nondesire. Anything beyond these utmost essentials of rice, bucket, water, pail distracts from Enlightenment. Buddhahood can be known in a few square yards of garden equally as in the sutras, lotus ponds, rituals, or a life of compassionate deeds. There are many paths to the Buddha, just as in the tsuboniwa, there are many perspectives of view. In the garden at the temple of Sorenji on the outskirts of Kyoto, the stones were set flat side up so the snow would remain longest on them. Such a placement symbolizes how embracing nature can be as it resists the encroachments of moss, root, shrub, fern, and yet how tender that embrace is as the ephemeral snow yields away its presence in furtherance of life. The significance of simplicity is that one never tires of it. At the Ryojuin Temple the use of white—noncolor—in a garden of spare monohues converts color into shape. The sense of colorness is absent. A species of white rhododendron is cross-bred specifically for this effect. The fact that all this planned purpose is set off to the side in a raked stoned garden conveys an unmistakable message: the noncolor of Illumination turns the sparrowy hues of being and meaning and figure and wish into not the hues of being, but the tints of transition. Seeing what is there is believing what is not: there is no such thing as casual. All this contemplative void-worship is radically reversed when the book comes to the courtyard gardens in the townhouses of well-off merchants. Merchants are rarely attracted to the minimal in any society. In their gardens is not the shunning of delusion but the embrace of decorativeness. Tasteful, to be sure, but the effect is many elements vying with each other for each its share of your attention span. Townhouse gardens seek not to edify or catapult into contemplation, but to relax and calm. They transport the intimate beauties of nature into the heart of the home, and thus—so the purpose goes—into the dweller. Instead of karuna—action taken to diminish the suffering of others—that is the garden of the temple, the residential garden is ohana—sharing undertaken to maximize the articulation of self. And it is hard to fault the merchants for their pride. With wealth came the best of Japan’s arts—ikebana, scrolls, ceramics, tatami, bamboo furnishing, shoji, lacquered wood, ink brushes, all those delicious crafts that make the country the subject of so many lovely picture books. Merchants do not relinquish with their gardens, they embrace. You begin to see utility objects converted into decor objects, specifically to be not used—water basins, bamboo cups, and, for the first time, tori or stone lanterns. Costly steppingstones (often in locations where they can’t be stepped on) made of rock imported from distant quarries take the place of the natural indigenous rocks found in temple gardens. Size—or rather oversize for effect—becomes a preoccupation, the way the well-to-do convey substance with overimage pretty much all over the world (ever see a small luxury car?). This usually happens with tori lanterns, which sometimes are overdimensioned to twice the size needed for a well-proportioned garden. Why? The significance of the stone lantern is its placement. Where it stands is a balance point between the thicket of the flower and plant and stone and the sky. The “eye” of the lantern ends the garden and begins the sky. Oversizing it draws attention to the lantern itself rather than the plane at which it divides garden from sky. The intent can only be drawing attention to an object for the object’s sake, which then in turn reflects on the assets of the owner. It is significant that tori do not occur in the temple and shrine gardens in the book, being inimical to the temple garden’s point. Domestic devotion usually shows up as ornamentation over abstraction. In townhouse gardens this occurs in juxtapositions of the best of Japan’s art forms—ikebana flower arrangements, tansu, painted folding screens, calligraphy on scrolls—adjacent to the tsuboniwa. In a temple garden there must be no distraction from the garden itself. It is hard to escape the notion that in Japan devotionalism occurs as ornament of surface. There is a shift in attention from emptiness and space to detail and volume. Absence of significance is not the goal, but rather significance of significance. Not to say that a townhouse garden can’t simplify. In one garden, a single stone lantern amid seven large bamboos instantly achieves the irreducible. It is like seeking the perfect poem by arranging seven words into a shape. The artist Keinen Imao designed his personal garden using the traditional elements—stone lantern, water basin with bamboo cup for washing the hands, carefully arranged stones, kutsunugi stone (a special shape from a handful of quarries all over Japan) to sit on while removing footwear, and two small trees. None of this is remarkable—until the sun shines down through the leaves of the trees, creating a play of leaf- and twig-shaped shadows on the ground. To Keinen Imao, the garden was these shadows, not the other objects in view. [Then search his name on the Web and you will see why. He all but lived among the leaves. (See especially https://www.artelino.com/archive/art_object.asp?evt=2&rel=11.] Damp scented air, zephyr, dust of snow, shaft of light: These are the merchant garden’s spiritual refreshment amid the crowded, hyperbolic ekistics of a city, the ekistics of too much thing and too little time. Morning is brief. Evening is brief. Light is brief. But a tsuboniwa is not brief, even though any one gaze may last for only a few moments. It is not brief because it is not of time. Landscapes for Small Spaces is a masterwork. Consider the physical production before even opening the book. It has overwide jacket flaps, reaching almost to the gutter; a generous expanse of space on which the jacket flap text floats gracefully. Most dust jacket flaps cram the text so tightly you can’t help but think of life in a telephone booth. Once inside, although there is no further mention than a small box on the copyright page, the book is printed in something called Diamond Screening, “a technology that enables the reproduction of color artwork and photography which far surpasses the quality achieved by traditional printing methods.” Indeed so: the wood floors of the Honen’in Temple on pp. 32–33 have been walkworn and waxed to such blackness that the very few reflections coming off them are a printer’s nightmare: large expanses of incrementally blending blacks and dark grays are broken by equal expanses of brilliantly whitewashed walls. Yet even at the far end of the halls in this double-page spread you can see undulations in the boards that perhaps even the eye might not notice. There are deep blacks and there are deeper blacks, and this printing process shows them all. There are less obvious touches, too, such as the ability of a large-format camera (apparently a 4” x 5” view camera in some shots) to render images sharper than the same scene seems to the eye. Kodansha produces books that will still have something to say a century from now, and then, as now, will say it well. However, this book lacks an important necessity: a bibliography. Here is a brief starter biblio if you want to pursue this subject a bit more:

© 2002 by Dana De Zoysa for Curled Up With a Good Book |

|

|

|

Click here to learn more about this month's sponsor! |

|

| fiction · sf/f · comic books · nonfiction · audio newsletter · free book contest · buy books online review index · links · · authors & publishers reviewers |

|

| site by ELBO Computing Resources, Inc. | |

For those who will never be invited to Exhibit A—the tea ceremony—Japanese gardens are Exhibit B. The gardens built abroad for Western eyes veer into caricature with moon bridges, koi ponds, multiple stone lanterns, pagodas, and tea houses. The real gardens are anything but a caricature. There are two basic types: outdoor and indoor. For each of these there are garden styles for palaces, shrines, and temples; gardens styles for townhouses; and styles for public places. To the casual eye all these look much alike. Look deeper, though, and they are quite different.

For those who will never be invited to Exhibit A—the tea ceremony—Japanese gardens are Exhibit B. The gardens built abroad for Western eyes veer into caricature with moon bridges, koi ponds, multiple stone lanterns, pagodas, and tea houses. The real gardens are anything but a caricature. There are two basic types: outdoor and indoor. For each of these there are garden styles for palaces, shrines, and temples; gardens styles for townhouses; and styles for public places. To the casual eye all these look much alike. Look deeper, though, and they are quite different.