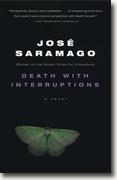

Death with Interruptions

Jose Saramago

book reviews:

· general fiction

· chick lit/romance

· sci-fi/fantasy

· graphic novels

· nonfiction

· audio books

· author interviews

· children's books @

curledupkids.com

· DVD reviews @

curledupdvd.com

newsletter

win books

buy online

links

home

for authors

& publishers

for reviewers

|

Death with Interruptions Jose Saramago Mariner Paperback 256 pages September 2009 |

|

Click here to read reviewer Max Falkowitz's take on Death with Interruptions. It is nearing the end of the first day of the New Year, and nobody has died. The Queen Mother, gently slipping away for months, was expected to make the New Year and that is all, but here she is, alive and, not quite well, but alive. Nobody has died in car accidents, though accidents occurred. And cancer, heart disease, and strokes, those hungry vicious assassins, have claimed a grand total of zero. What a wonderful opening to a year, what a herald of positivity.

People are, initially, understandably pleased at this unexpected providence. Having lived, until those days of confusion, in what they had imagined to be the best of all possibly and probable worlds, they were discovering, with delight, that the best, the absolute best, was happening right now, right there, at the door of their house, a unique and marvelous life without the daily fear of parka's creaking scissors, immortality in the land that gave us being, safe from any metaphysical awkwardness and free to everyone. It is strange that the absence of death was limited to the borders of this nameless country, but it is of course stranger still that death itself has been bested. Poets imagine the limitless epics they can write, musicians the albums they can compose into infinity, and business-minded people the joys of compound interest when eternal life beckons. But eternal life is not without its problems. The sudden blessing that has fallen upon the nation turns out to be something very much approaching a curse. Terminally ill patients will remain gravely ill, forever, their families forced to care for them from now until they, too, succumb to some sickness and require assistance. What happens when the pool of young, healthy people becomes outweighed by an endless collection of ancient, dying but never dead relatives? The nation would become crippled with an epidemic of illness. Life insurance becomes something of an off-color joke, with hundreds of thousands canceling their policies. Heaven becomes the greatest desire a person can never attain, with the attendant problems this causes the Catholic Church. Eternal life seems first a paradise but very quickly is realized as a Hell. People need to die; beginnings must inexorably move toward an end. Saramago sets his fiction in countries that are never identified, populated with people without names. He rarely personalizes his ministers and priests and cellists and television directors, instead choosing to create an intimate bond with the reader by way of the narrator. We are comfortably prodded through deep theological and philosophical problems by the kindly, genial, somewhat absent-minded and certainly roundabout Saramago. That the novel is a story is often alluded to and even more often baldly stated, with Saramago admitting that this book adds a little story to the great tomes and creaking apocrypha that surrounds death, dying, and what happens afterward. Because we are unambiguously aware that this is a story and not a text presented as fact, Saramago becomes a wise old man sitting around a fire dispensing his wisdom, coating the conceptual difficulties of his text with the sweet, easy-to-digest coating of homely sayings, chattering digressions and playful asides. Bitter pills need not always taste so bad. Sentences unfold like elaborate acrobatic performances, twisting and turning where you least expect it, though the effect is marvelous to observe. Absent from his writing are dialogue marks, semi-colons, and often even capital letters, but the subtle tone shifts and liberal use of commas create a flow of text which every reviewer is bound to refer to as 'musical'. But it is; Saramago's sentences are both as delicate and muscular as a Bach cello concerto. His paragraphs alternately slink, scurry and slide across this central problem of death and dying. Just as the premise threatens to exhaust itself, and the problem of 'what next' begins to rear its head, Saramago shifts gears and repositions the novel to become, of all things, a love story. death never Death comes to an agreement with the nation, stating that she will send individuals a letter a week before their designated death date. This, rather than calm everyone by returning to something close to normal, sets off a wave of national despondency and inertia. People become paralyzed with worry that the postman will bring them a violet letter written in a 'chaotic hand.' Love enters when a cellist breaks the unspoken covenant between the living and death by refusing to accept his letter it bounces back to death's study, unopened and unknown by its recipient and by having his fiftieth birthday, an event determined from his birth as something that could not occur. death, intrigued, watches the cellist as he lives his life and, surprisingly believably, begins to fall for him. death is a female, which helps to explain the simultaneously delicate and harrowing touch that passing away can bring, and death, it seems, can be lonely. death has never really observed humans at any time other than their dying, which perhaps explains her fascination with this we are told repeatedly overwhelmingly ordinary man. Her growing obsession begins first from her will being thwarted but stays thanks to the conundrum a living, breathing person represents. Death with Interruptions Originally published on Curled Up With A Good Book at www.curledup.com. © Damian Kelleher, 2008 |

| Also by Jose Saramago: |

|

|

|

Click here to learn more about this month's sponsor! |

|

| fiction · sf/f · comic books · nonfiction · audio newsletter · free book contest · buy books online review index · links · · authors & publishers reviewers |

|

| site by ELBO Computing Resources, Inc. | |

Jose Saramago, the grand old man of Portugeuse letters who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998, has written a deeply probing, though narratively casual, novel concerning death and her absence.

Jose Saramago, the grand old man of Portugeuse letters who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998, has written a deeply probing, though narratively casual, novel concerning death and her absence.