author interview

book reviews:

· general fiction

· chick lit/romance

· sci-fi/fantasy

· graphic novels

· nonfiction

· audio books

· author interviews

· children's books @

curledupkids.com

· DVD reviews @

curledupdvd.com

newsletter

win books

buy online

links

home

for authors

& publishiss

for reviewers

|

|||||

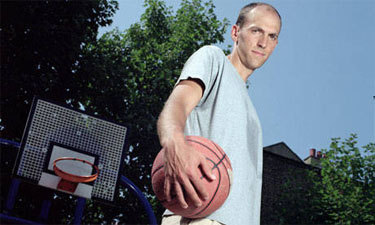

Author Ben Markovits talks about his latest novel, Childish Loves Interviewer Michael Leonard: Childish Loves Ben Markovits: When I was about fourteen, my family moved to London for a year. We lived near a little secondhand bookstore on a cobbled alley, in which you could still buy 19th-century editions of poetry, with uncut pages, for a couple of pounds. This is when I started buying books, and reading in earnest. And one of the poets I read was Byron. By the time I came to write Imposture (my third novel), I had worked out, more or less, the kind of characters I liked to write about. Mostly failures of one sort or another, and Byron seemed a very vivid foil for me to set off their qualities. But the trilogy is also about the love of books, a love I associate with late childhood, when many people begin for the first time to read intensely. The seed for your new novel stems from events in Byron’s life that occurred years apart. How did those events become the foundation for Childish Loves I didn't want to write a big sprawling novel that tried to swallow the whole of his life. Biographies do that. I wanted to write stories. Byron, of course, is famous for his sex-life, but I thought that if you looked at some of his sexual encounters in detail, one by one, a different picture of his character might emerge. He himself liked to claim that he had been more ravished than anyone since the Trojan War, and his most famous libertine character, Don Juan, is in fact rather passive sexually—an observer and a victim.

Childish Loves Well, I read a lot of Byron, which was one of the perks of the job. Not just his poetry, but the famous letters and journals. Then again, I've been reading him since I was fourteen years old, I studied him in college and in grad-school, too. There are many wonderful things about his style, which you can learn from as a writer even if you're not trying to capture his voice. The way he writes vividly without much reliance on adjectives or metaphors. His abrupt changes of pace. His conversationalism. The way he tried to widen the scope of what literature can talk about. In “Beppo,” he advises people traveling to Italy during Lent do bring ketchup with them, because the food's boring. But he's also making a larger point: that ketchup is as much a part of our lives as birds, hills, clouds, love, etc.

What is the significance of the title “Childish Loves”? How does it relate to the other titles in the series? “Childish Loves” refers to many things in the book. One of them I've already mentioned: the love of books, which I felt most strongly when I was about fifteen, sixteen, seventeen years old. Also, the love of childhood, and children. I've got a couple small kids now, and they often stir up memories, which had been covered in dust, of my own early years. It's hard to be sure, it's easy to misremember, out of nostalgia, but I think the world felt more vivid and real to me when I was a kid than it does now. But there's also a more uncomfortable implication in the title, which refers to Byron's own love of children, which could be sexual on occasion. He himself was probably abused as a child, by his nurse—his sexual indoctrination came early. And there seemed to me something awkward about the relationship, between innocence and attraction, that was worth looking into. Do you think Byron—and by association Peter Sullivan—craved fame and attention? Were their lives fulfilled? Good question. I meant to set them up on opposite ends of a spectrum. Byron's life was rich in incident, he was famous, admired and loved. Peter repressed most of his worldly longings and isolated himself as much as possible from other people. Most of us probably live somewhere between these two poles, which is where my own character is situated in the novel. But moderation involves its own complications, which I try to show in the book. To answer your question more simply: I think Byron was probably more fulfilled than Peter. Peter grew up isolated his mother his only friend, and Byron, his mentor. How would you describe the emotional complexities between Peter and his mother? What gave you inspiration for the other characters that appear throughout Childish Loves I don't know that I can say anything about their relationship that isn't in the book. There's probably a wider range of types in Childish Loves I see Peter Sullivan and Lord Byron as mostly linked by their repressed desires. Certainly Peter was subject to the social strictures of our time while later in life Byron seemed content to flout them. What do you see as their similarities and differences? Both Peter and Byron struggled with difficult mothers. But Byron was a lord, and handsome, and could easily escape her. Peter escaped his mother, too, but partly by retreating into his own shell. Both Peter and Byron had no relations with their fathers. They both, as Dickens once put it, read for life. There the similarities probably end, but one of the things I wanted to think about in the novel is the act of sympathy that could make Peter respond to Byron's writing and write about him in turn. There's this wonderful line in one of Byron's letters: 'I only go out to get a fresh appetite for being alone.' For Peter, that appetite doesn't need any refreshing. You set up a number of distinctive challenges in Childish Loves One of the things I try to do in the book is expose the historical scaffolding on which the novels rest: I want to show my work, as they say in math class, and not just the answers. Often, at readings, people would ask me how much of what I had read was true. So this truth-question drives some of Childish Loves How challenging was it to merge the stories of Byron and Peter into the story of your own fictional self? The trouble with writing a split narrative is that you have to solve all the problems of a novel several times. Finding a style that will carry the story. Finding a story, etc. There are six sections in the book and I tried to write each so that it worked on its own. But they also had to contribute to the overall narrative–they had to add up to something. Of course, this is more or less how the trilogy works as a whole. I wrote Childish Loves I was struck my how so much of the novel is illusory, a play on reality, from Byron’s first sexual dawning at Newstead to his affair with Edleson at Canterbury, so much is hinted at. How much to do you think his sexual peccadilloes influenced the darker side of his literary life? His poems and plays often hint at some dark, abiding sin. Whether he had in mind his affair with his half-sister, or his relations with men, I don't know. Probably both. Sin is part of what his first readers found attractive about him. Thinking back to the second novel in the series, A Quiet Adjustment, Annabella Milbank was Byron's muse, but his affair with his half-sister Augusta Leigh drives him to distraction. To what extent do you think his encounters with women were critical to his work? He wrote a lot of love poems, some of them famous. “Maid of Athens” (though the maid was more of a girl when he met her), “She Walks in Beauty,” even “So We'll Go No More A-Roving,” is about his relations with women. Not to mention the great love scenes in “Don Juan.” But there are also many less famous poems about love, which I grew up reading and admiring for their simplicity of style: “And Thou Art Dead, As Young and Fair” is one example. A few years ago, Fiona MacCarthy's biography of Byron came out, and the publishers tried to sell it as the homosexual Byron. In fact, the book presented a much more evenhanded and accurate picture. Byron had important relationships with both sexes, but I think the one that mattered most to him, of either sex, was his relationship with Augusta. Do you think Byron’s inappropriate relationship with Augusta haunted him through the years? It mattered a lot to him. He felt happy and natural around her, and when she eventually withdrew sexually from him, it made him very miserable – he took out some of his anger on his wife. And then his wife worked hard to extricate Augusta emotionally from Byron, and this was another and enduring source of pain. I thought that Lady Caroline Lamb’s attraction to Byron was interesting. If he loved Annabella why was Byron drawn to Lady Caroline, and she to him? Why did Lady Caroline jealously circulate rumors of marital violence, adultery, sodomy, and incest with Augusta Leigh? Yes, it's curious, isn't it. Because even if he didn't love Annabella (or Lady Caroline very much, after the initial infatuation), he was clearly attracted to both. Annabella continued to get under his skin, and even after his divorce, when it was clearly impossible, he sometimes thought of reconciling with her. Partly, she was tied up in his mind with what he called his Grandmother's review, the British -- with living in England, and the years of his fame, etc. But he was also very attracted, I think, to her smarts and even her prudery. Byron had a strong self-abnegating streak. Caroline, of course, attracted him for very different reasons. Her sense of risk, and own reckless infatuation with him, and also, I'm sure, her boyishness. So much about the trilogy involves deception. In the first novel, Imposture, there’s Polidori’s duplicity with Eliza along with her own game of pretense. In A Quiet Adjustment, there’s Annabella’s denial over the prospects of love and fame with Byron. In Childish Loves That's part of the problem with fame–you become a means to other people's ends. There's something strangely belittling about celebrity. And part of the point of Childish Loves Byron and Polidori seem so dependent on each other. Later, the Doctor has literary aspirations of his own. How would you define Polidori’s feelings for the man who both charms and betrays him? In my book, Polidori has moments of honesty, in which he can admit to himself that Byron is not only the greater writer, but that Polidori himself is something of a lost cause, a nuisance to other people and a thorn in his own side. Of course, this realization doesn't make him any happier. But it must have been very galling, and exciting, too, for the real Polidori to see his story “The Vampyre” flying off the shelves. Byron was a larger-than-life figure and at the time was considered to be a "morally fractured" individual by most of London's society. Do you think he reveled in his promiscuous notoriety? Yes, sometimes. But he could also be very sensitive and shy, and the fame probably cost him something, too. He had that foot, of course, to be embarrassed about. All three sections in Childish Loves He probably gets the most sexual fulfillment in the university section; maybe that's not uncommon. But it seemed important to me to show him in various lights. He was both a victim and a seducer, and could also hold back on occasion, and refrain. It's not clear to me in which role we sympathize with him most. That's one of the questions I try to ask in the book. All three of these sections of Childish Loves I'm a very bad historian, but I like the literature. So I read a lot of Austen, I read 'Monk' Lewis, I read Scott and Byron, over and over and over. Why do you think Byron got caught up in the fight for Greek independence? Do you think he finds peace at the end of his life? I think he wanted to get caught up in something important, something great, and Greece was the closest thing. But I don't think he found peace. I think he made the best of a bad job, with failing personal resources, and probably knew as much by the end. Throughout the series, we get a distinct feel for Byron’s poetry—and Peter Sullivan’s love of it. What was it about Byron’s poetry that separated his work from other poets? Wordsworth talks about the importance of using the real language of men, but I don't think anyone in the period comes closer to doing that than Byron. Of course, as soon as you talk about language, you need to talk about class, too, and Byron's voice belongs to a distinct class and period, but it's wonderfully natural and alive, even today. Just compare Byron's “Beppo” to Keats's “Ode to a Nightingale”, or Shelley's “Prometheus Unbound,” or even Wordsworth's “The Prelude.” “Beppo” describes parts of ordinary life that none of these other poets ever found a way to address in their poetry. When all is said and done, what were the most influential years of Byron's life? What do you see as his most accomplished poem? Out of all of his poetry, do you have a favorite? I think he got better as he got older, though I'm very fond of parts of “English Bards and Scotch Reviewers” and “Hints from Horace.” But “Beppo” seems to me wonderful, and “Don Juan” is full of great things. Byron had an odd career. He became famous for poems which many critics now consider second-rate, and was dropped by his publisher for his masterpiece, “Don Juan.” Many of the contemporary sections in Childish Loves Yes, I think of myself as American. I follow American politics and check up on American sports, even in England. And I go back to the States as often as I can. I love Austin, and it was a pleasure to write about Austin in the book. Also, it's not easy being an English writer. There are so many details, of culture and class and idiom, to get wrong. That's part of the appeal of Byron to me. He allows me to write about an aspect of English culture that I have as much access to as the English. How do you think your trilogy has added to our conversation about Lord Byron? What have you most learned about the poet and his work? I suppose that's not for me to say. There's a little scene in Imposture, in which Eliza visits Polidori in his rooms, thinking that he's Byron. And Polidori fails to disillusion her. He lives up to the role. This is the contradiction Byron suffered from, Polidori thinks: between the amusement one feels at playing a part and the really tender feelings it evokes. I think that's true of Byron. Do you have a new novel in the works? I'm working on something contemporary at the moment. Set in America. What would you like your readers to most take away from the Lord Byron trilogy? I hope it gives them pleasure, and deepens their sympathies for the people involved.

|

|||||

| fictionnsf/f · comic books · nonfiction · audio newsletter · free book contest · buy books online review index · links · · authors & publishiss reviewerss |

|

| site by ELBO Computing Resources, Inc. | |