The Good Soldier Svejk

Jaroslav Hasek

book reviews:

· general fiction

· chick lit/romance

· sci-fi/fantasy

· graphic novels

· nonfiction

· audio books

· author interviews

· children's books @

curledupkids.com

· DVD reviews @

curledupdvd.com

newsletter

win books

buy online

links

home

for authors

& publishers

for reviewers

|

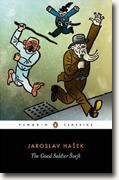

The Good Soldier Svejk: and His Fortunes in the World War Jaroslav Hasek Penguin Classics Paperback 784 pages December 2005 |

|

Can humor translate across time and distance? While reading Jaroslav Hašek's unfinished World War I satire, The Good Soldier Švejk

The first part of the novel is episodic, with the individual chapters having little to do with one another other than a few sentences at either end that serve as segues into a new setting. Švejk is arrested, set free, arrested, set free, put into a mental asylum and set free, then arrested once more. There are many, many references to Czech history and culture throughout, and the translator has helpfully included notes to explain just what it is everyone is discussing. It is here that the major problems with the novel raise their heads. It is reasonable to expect that most readers in America, the United Kingdom and Australia would not be particularly familiar with Czech culture, which means that a massive number of the jokes and references - no matter how well explained by the translator - simply go unnoticed or, if noticed, unappreciated. Hašek is very much a writer of his nation, and the novel, to an outsider, suffers because of this. Another problem lies with the character of Švejk. For the first part, and most of the second, Švejk is a fool, bumbling through his adventures without developing much of a personality beyond that of an imbecile. It is easy to understand why everyone is mad at Švejk and interprets him incorrectly - it is because he is blissfully, wilfully stupid and ignorant. Unfortunately, we don't much care what happens to him, and there is a sense by the end of the first part that perhaps it would be better if he were to be hidden away in a prison, after all. Happily, the novel comes into its own in the third part and retains its momentum throughout. Švejk settles down, as it were, staying within easy grasp of a number of major characters. He becomes the batman of Lieutenant Lukáš, and the archenemy of Lieutenant Dub. Švejk stops being merely an imbecile and instead becomes an immovable force, a bland structure that deflects and reflects criticism, responsibility and problems. He represents the common man's struggle to avoid the grand machinations of war. Švejk, while patriotic, does not really wish to die fighting for his country. The Lieutenant Dubs of the world, for all their ambition and greed, wish nothing else. Švejk deflects the higher levels of military command by playing the fool, by putting one over everyone who wishes to see him and the other men dead. Lieutenant Dub acts as a humorous and effective villain. He is also a fool, something of which the reader and Švejk are both aware. This long quote is a good indication of the personalities of both Švejk and Lieutenant Dub, and the way the two play off each other throughout the last half of the novel: Lieutenant Dub stared in rage at the serene face of the good soldier Švejk and asked him angrily: 'Do you know me?'Hašek was unable to finish the novel before he died. It cuts off abruptly mid-chapter, near the start of Part IV: The Glorious Licking Continued. This is a shame, because the third part of the novel is by far the greatest, and what there is of the fourth indicates that the quality of writing and pitch-perfect satire would continue. Švejk is an imbecile and a fool in the first two parts of the novel, but he becomes something more in the last half. He is a soldier at the mercy of the currents of war. He knows that it is important that he survive, but also that his superiors do not care for him at all. He must look after himself with the only tools he has at his disposal - the exposure of fools and foolish behavior. Švejk is a clear voice in the hectic, mad cacophony of war. But there is more. Švejk never actually participates in war, and the conflict of armies and soldiers is not present within the novel. More than that, there are no great scenes of regular military life. Švejk's career could have been situated in any setting, for it is the importance of the satire that pushes the novel forward. Hašek exposes the folly not just of war but of structure and order, of the deadening elements that necessarily come from bureaucracy and chains of command. To answer the question originally posed - Is humor translatable? Based on The Good Soldier Švejk Originally published on Curled Up With A Good Book at www.curledup.com. © Damian Kelleher, 2007 |

|

|

|

Click here to learn more about this month's sponsor! |

|

| fiction · sf/f · comic books · nonfiction · audio newsletter · free book contest · buy books online review index · links · · authors & publishers reviewers |

|

| site by ELBO Computing Resources, Inc. | |

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, World War I has begun. Švejk, a bumbling, 'imbecilic' Czech, wishes to become a soldier and serve his country. We follow him as he wanders about, falling in and out of mischief and adventure.

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, World War I has begun. Švejk, a bumbling, 'imbecilic' Czech, wishes to become a soldier and serve his country. We follow him as he wanders about, falling in and out of mischief and adventure.