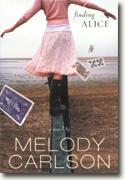

Finding Alice

Melody Carlson

book reviews:

· general fiction

· chick lit/romance

· sci-fi/fantasy

· graphic novels

· nonfiction

· audio books

· author interviews

· children's books @

curledupkids.com

· DVD reviews @

curledupdvd.com

newsletter

win books

buy online

links

home

for authors

& publishers

for reviewers

|

Finding Alice Melody Carlson WaterBrook Press Paperback 384 pages September 2003 |

|

|

I had no idea Finding Alice was categorized as a Christian book. As this is not a market I follow, if I had, I might have reconsidered reading it. WaterBrook is an "autonomous evangelical religious publishing division" of Random House, Inc., I discovered. That said, writer Melody Carlson, who has penned some 90 books for children, teens and adults, has handled the issue of schizophrenia gently and kindly; her book does not feel like she is proselytizing.

Alice breaks down while living at college, begins having visions and hearing voices. She especially hears a woman named Amelia: "She's my guardian angel. She tells me things," she admits. She is institutionalized at Forest Hills, where she is treated traditionally, drugged heavily and sometimes restrained. But she makes an escape, attends a demonstration with new acquaintances, and ends up living on the streets for a time, not taking any medication, making friends especially with two young gay men. The three take care of each other. She discovers a starving stray kitten, takes it into her heart and arms, and her new friends tell her about "The Cat Lady," Faye, who takes in strays. Alice goes in search of her. This is a fortuitous move. Faye takes in more than cats; she takes in Alice, with no luggage, no meds, nothing but a skinny cat and one dirty set of clothes. Obviously, Faye can see beyond Alice's condition. They live together for some time, and both Alice and her cat, Cheshire, do relatively well. The cat constantly sits on her lap. Alice is able to maintain a somewhat "normal" relationship with Faye on some days; she goes grocery shopping and prepares easy meals. She slips in and out of lucidity. After a few days, Faye introduces Alice to her nephew, Simon, a young man who just happens to work at an unusual, forward-thinking mental health facility, and he takes her there to see what it is like. Although when she first visits, Alice goes only to decorate for a Christmas party and later to attend the party, she eventually does consider living there, as most the residents are artistic and only mildly medicated. The man who runs the clinic is known for his "alternative" treatments -- fewer drugs and more therapy and art -- that appear to work for many. The book seems quite realistic and well researched. Like Alice, most people who develop adult-onset schizophrenia do so in their late teens or early adult years. Like Alice, many are terrifically intelligent and creative -- witness John Nash and Virginia Woolf, for starters. One motif that appears throughout the book is that Alice finds a kindred spirit in Alice in Wonderland, her disappearing into a "rabbit hole," her make-believe lands. She names her cat "Cheshire. " She refers to Forest Hills as "Wonderland". The author weaves this fantasy world -- and the voices Alice hears -- throughout the novel quite successfully. The ending is both uplifting and disappointing. A car accident changes Alice's and Simon's lives, and during their recovery, they make various decisions. But the conclusion seems the least likely event of this book, and almost makes it seem like a fairy tale, say like Alice in Wonderland or Cinderella. Nevertheless, this author is to be added to the growing number of writers who are attempting to educate readers about mental illness. For this reason alone, the book is worth reading. Originally published on Curled Up With A Good Book at www.curledup.com. © Deborah Straw, 2004 |

| Also by Melody Carlson: |

|

|

|

Click here to learn more about this month's sponsor! |

|

| fiction · sf/f · comic books · nonfiction · audio newsletter · free book contest · buy books online review index · links · · authors & publishers reviewers |

|

| site by ELBO Computing Resources, Inc. | |

In fact, the protagonist, Alice Laxton, who tells her story in first

person, grew up in a repressive, born-again Christian household that is

not drawn sympathetically in the novel. After she leaves home for

college, Alice has little contact with her mother and brother, but she

is relieved when her mother leaves that church for one with a more

mainstream agenda. That said, nothing much in the book is overtly about

religion. Jesus is only occasionally mentioned. It is rather about

Alice's changing mental life; as a senior in college, she descends into

schizophrenia and becomes progressively lost to her former life and

relationships.

In fact, the protagonist, Alice Laxton, who tells her story in first

person, grew up in a repressive, born-again Christian household that is

not drawn sympathetically in the novel. After she leaves home for

college, Alice has little contact with her mother and brother, but she

is relieved when her mother leaves that church for one with a more

mainstream agenda. That said, nothing much in the book is overtly about

religion. Jesus is only occasionally mentioned. It is rather about

Alice's changing mental life; as a senior in college, she descends into

schizophrenia and becomes progressively lost to her former life and

relationships.