Wizard of the Crow

Ngugi Wa'Thiong'O

book reviews:

· general fiction

· chick lit/romance

· sci-fi/fantasy

· graphic novels

· nonfiction

· audio books

· author interviews

· children's books @

curledupkids.com

· DVD reviews @

curledupdvd.com

newsletter

win books

buy online

links

home

for authors

& publishers

for reviewers

|

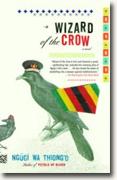

Wizard of the Crow Ngugi Wa'Thiong'O Anchor Paperback 784 pages August 2007 |

|

If you’re like me, you may also be unfamiliar with African literature outside Chinua Achebe. I requested this book knowing nothing about Ngugi, hoping to expand my literary horizons. I wanted a different style of prose, one that was distinctly non-American, non-European, and non-Eastern. I was also intrigued by the notion of a satirical dystopia written as an epic folk myth. I very much wanted to like this book.

Ngugi flirts substantially with the ridiculous to make his point hit home. For example, the Ruler’s cabinet surgically enhance their bodies. The foreign affairs minister enlarges his eyes to become the eyes of the Ruler; in retaliation, the minister of information enlarges his tongue to be the voice of the ruler, only to find that he must enlarge his mouth to retain the ability to speak. Or take the dogged readiness with which people believe the “magic” of the wizard. While the novel abounds in such peculiarities, which provide the bulk of the humor-satire edge, the absurdity really hits home when considering Aburiria in context of the greater world’s eye. We’re privy to precious little knowledge about the real state of life in Africa besides what we see in melodramatic news stories. It is a place about which most of us must plead ignorance. It seems that Ngugi’s point is not necessarily that this is what goes on there, but rather that this could be going on there without our knowledge. Wherever the Ruler goes, he gets neither press nor attention (except for rumors about him being pregnant, fitting in with a tabloid interest in world news). When appealing to the Global Bank for funds for Marching to Heaven, he is treated with the most obvious veiled superciliousness. His people get no further attention. American ambassador Gabriel Gemstone’s (get it?) only concern about the Ruler’s harsh treatment of his people and the developing quasi-civil war is the way it effects America’s image. One actually feels sympathy for the Ruler when he angrily notes that back during the Cold War, the Americans loved him for mass-murdering communists; now he is chastised. Aburiria is a country no one cares about, an isolation made all the worse by the fact that there are many in the novel who want to be just like the whites who treat them so poorly, a disease the wizard calls “white-ache.” This is the bite of Wizard of the Crow Regrettably, the novel fails in many other respects. It’s significantly longer than it has to be, and the plot-driven narrative feels painfully clunky. While suggesting a complex magical world is usually a good thing in these modern folktales, there must be a consistency to it. Take for example, the world in Neil Gaiman’s Anansi Boys: it is cleanly mysterious and just comprehensible enough. Wizard of the Crow Another concern that I feel needs addressing is the writing style. It is indeed a unique style, neither Western nor Eastern, and while this may earn it praise for “sticking to its roots,” that doesn’t make it good. Ngugi has a tendency not just to leave necessary things unexplained, but to explain things that necessitate no such explanation, like basic motivations for actions that are easy to infer, like the logic behind the ministers’ jockeying for favor. At other points the narrative is painfully blatant: “…the movement gave purpose and direction…Most politicians want to master people. But your people want to master themselves before they can master others. I want to work with you.” There’s little to capture the imagination in these words; this is the case for most of the text. Moreover, the writing itself feels awkward and stilted. The prose is very polite and feels far too much like a non-native English speaker trying to find the right words and convey them with dignity. This may be a fault of English not being able to capture the original text’s nuances, but that doesn’t change the bewildering word choice and expository style. I did very much want to like this book. And it does pack a message Americans should care about, and presents it in a relatively unconventional, curious, and sometimes funny and entertaining way. But the failings of the narrative prevent the experience from feeling like it is worth the struggle. Wizard of the Crow Originally published on Curled Up With A Good Book at www.curledup.com. © Max Falkowitz, 2007 |

|

|

|

Click here to learn more about this month's sponsor! |

|

| fiction · sf/f · comic books · nonfiction · audio newsletter · free book contest · buy books online review index · links · · authors & publishers reviewers |

|

| site by ELBO Computing Resources, Inc. | |

To its credit,

To its credit,