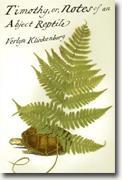

Timothy; or, Notes of an Abject Reptile

Verlyn Klinkenborg

book reviews:

· general fiction

· chick lit/romance

· sci-fi/fantasy

· graphic novels

· nonfiction

· audio books

· author interviews

· children's books @

curledupkids.com

· DVD reviews @

curledupdvd.com

newsletter

win books

buy online

links

home

for authors

& publishers

for reviewers

|

Timothy; or, Notes of an Abject Reptile Verlyn Klinkenborg Knopf Hardcover 192 pages February 2006 |

|

It’s a great irony that the remains of Timothy– a kidnapped female tortoise which weathered a 53-year exile in 18th-century England – should have ended up, in a sense, re-kidnapped when her shell was consigned to London’s Natural History Museum, where it remains. She has been given voice by writer Verlyn Klinkenborg, who called upon a trove of period research, including detailed records kept by her ultimate owner, Gilbert White, a Hampshire clergyman and avid amateur naturalist whose The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne was published in 1789.

Had Klinkenborg actually been around in that distant century to speak as eloquently in the venerable tortoise’s voice as he does in this remarkable book, I like to imagine that Timothy might have been returned alive to her sunny rock on the Mediterranean coast by dint of his pleading her history: of being snatched, bagged, and brought to sun-challenged Britain. It was her fate, it seems, to have caught the eye of a sailor possibly hoping to profit from a fad among British country clerics. “I was fashionable, you see. . . Find a clerical establishment of a certain outlook and behold! Tortoise in the garden.” And, once plunked down on alien soil “what have I not survived? Winter after winter, drought and flood.” To which Klinkenborg might have attached this addenda: and survived personal insults, too, considered male by a half-century of English care-takers and characterized “most abject reptile and torpid of beings” in the writings of clergyman-naturalist White. The author’s central feat is conjuring, in the biblical phrase, a “voice of the turtle” that, while always entertaining and instructive, rises at times to a sort of wry, distilled eloquence. This is burnished by his skill in evoking the nature-attuned rhythms and rituals of 18th-century English rural life with its endless physical toil of planting and harvesting, caring for livestock, preparing rushes to be light sources and preserving summer’s fruits and vegetables for winter’s meals. Descriptions seem to merge into a collage of constant tasks: “A man in a dry year climbs sixty-three feet down Mr. Gilbert White’s well. Like a bat in a chimney . . . In the meadow the dairy-maid pitches herself beside a spotted cow’s udder. Leans her head against the flank. Two teats for the calf standing opposite . . . The thatcher, Richard Butler, laying bright new thatch. Clambers over the ridge-poles in the village . . . Shearer and sheep move almost as one. Cotillion of wool.”Klinkenborg’s prose also encourages a closer scrutiny of our own species and of those other beings of myriad and meritorious species with whom we share the planet. Will his enviable imagination and apt research result in further Timothy channelings? Or titles that incorporate a like theme of how far we’ve come from our rural roots but how frail and unformed we stubbornly remain? If so, those now besotted by the sentient tortoise of this wise tale will be grateful. Or, as rurals were once wont to say, “Much obliged!” The author writes for the New York Times and serves on its editorial board. Previous books include Making Hay, The Last Fine Time, and The Rural Life. Originally published on Curled Up With A Good Book at www.curledup.com. © Norma J. Shattuck, 2006 |

| Also by Verlyn Klinkenborg: |

|

|

|

Click here to learn more about this month's sponsor! |

|

| fiction · sf/f · comic books · nonfiction · audio newsletter · free book contest · buy books online review index · links · · authors & publishers reviewers |

|

| site by ELBO Computing Resources, Inc. | |

The author’s transmutation is from 21st-century homo sapiens to 18th-century aged, armored reptile. And that feat of imagining works! One proof is in readers understanding how Timothy would

have lamented a final interment which subjected her, if by then but a shell, to the stares of generations of museum-crawlers. Such gawkers, after all, are representative of a species she yearned to escape: “I wish to be out of human reach. Out from under the constant stir. Laborious turmoil of this breed. Endless bother of humans. . . Dizzying inability to bask or muse.”

The author’s transmutation is from 21st-century homo sapiens to 18th-century aged, armored reptile. And that feat of imagining works! One proof is in readers understanding how Timothy would

have lamented a final interment which subjected her, if by then but a shell, to the stares of generations of museum-crawlers. Such gawkers, after all, are representative of a species she yearned to escape: “I wish to be out of human reach. Out from under the constant stir. Laborious turmoil of this breed. Endless bother of humans. . . Dizzying inability to bask or muse.”