author interview

book reviews:

· general fiction

· chick lit/romance

· sci-fi/fantasy

· graphic novels

· nonfiction

· audio books

· author interviews

· children's books @

curledupkids.com

· DVD reviews @

curledupdvd.com

newsletter

win books

buy online

links

home

for authors

& publishiss

for reviewers

|

|||||

Luan Gaines interviewed Susan Holloway Scott, author of Royal Harlot: A Novel of the Countess Castlemaine and King Charles II Interviewer Luan Gaines: What was your inspiration for Royal Harlot: A Novel of the Countess Castlemaine and King Charles II Susan Holloway Scott: It’s hard to avoid Barbara Palmer’s name in any book, fiction and non-fiction, about the Restoration. Barbara is always depicted as evil incarnate, manipulative, shrewish, and acquisitive. Yet she remained Charles’s favorite mistress for nearly ten years, and maintained a cordial relationship with him until his death. There had to be more to her character than the ‘wicked witch’ she’s always painted to be and, liking a challenge, I decided to tell her side of the story. How would you describe Barbara Villiers’ relationship with her mother? How did that relationship determine Barbara’s course of action after her arrival at Ludgate Hill in 1656? Barbara’s mother, Mary Bayning Villiers, was a survivor. Born a wealthy heiress, she was married, widowed, and left a pauper with a child to raise in the middle of a Civil War before her eighteenth birthday. She chose next to wed her late husband’s cousin for protection, and sent her young daughter to be raised in the country. When that same daughter –– Barbara –– reappeared in her life as an inconvenient beauty with a wild streak, Mary’s reaction was to try to marry her off as soon as possible. There doesn’t seem to have been much real love between mother and daughter. Mary appears to have regarded Barbara as an unwelcome reminder of her past life, as well as an embarrassing disgrace as Barbara’s “career” progressed and she became the king’s mistress. My guess (and I admit it’s only a guess; there’s no hard historical proof) is that Barbara came to London hoping for a more loving relationship with her mother. When that was not forthcoming, she may have turned to men like the Earl of Chesterfield for the affection she wasn’t finding at home. Barbara quickly lays claim to a wanton nature, easily stepping outside the boundaries of convention. To what do you attribute Barbara’s cavalier attitude toward morality? Is she by nature a libertine? I suspect it was a combination of factors. Yes, I believe Barbara was by nature a woman who enjoyed her sexuality, but she also lived in a time and place that encouraged it. She grew to adolescence raised by distant caretakers, with little family influence or discipline. In London, she fell in with a society of other displaced, rootless children of Royalist aristocrats who had nothing much to do but to entertain themselves. For them, a life dedicated to pleasure-seeking was as much a political statement –– thumbing their collective noses at the Puritans in power –– as it was a way of passing the time.

For young Royalist women like Barbara, the exiled King Charles was a fabulous romantic figure, much like a modern movie star. At twenty-nine, Charles had begun earning a well-established reputation as a womanizer while still a teenager. He was tall, dark, handsome, nobly born (of course), with a tragic past to give him an intriguing melancholy.

By 1660, England is ready to embrace Charles as their monarch. How has the repressive Puritan rule affected the country in the difficult years before the Restoration? England under Cromwell was a somber place, ruled by conservative Puritan philosophy as much as by the Protectorate. There was no music, theatre, or art. Celebrations of frivolous holidays such as May Day and Christmas were forbidden. Churches had been “purified”, with choirs and other music banned, services purged of any faintly Roman practices, and stained glass windows smashed.

Charles has great plans for his Restoration Court. In what way does Barbara distract the king from affairs of state? At the same time, Charles is referred to as the Merry Monarch. Is it in his nature to avoid governance for pleasure? Charles began his reign as an idealistic king, determined to learn from his father’s mistakes. He made himself accessible to his people on a daily basis in a way no modern leader ever could be. Not only was he approachable in the public parks during his daily walks with his dogs, but also at worship, at the theatres, and sailing or swimming in the Thames. During the Great Fire, he didn’t flee to the safety of the country like most of his courtiers, but instead joined in fighting the fire himself, even passing buckets of water to douse the flames. He longed to heal his fractured country with a generous optimism that his headstrong people warily resisted.

Barbara takes a calculated risk when she becomes pregnant with Charles’ child. How does bearing the king’s children improve her fortune and the longevity of her relationship with Charles? The most bitter irony of Charles’s reign was his inability to sire a legitimate heir to his throne with his barren queen, while at the same time fathering at least a dozen children with his mistresses. Yet he was still a fond, loving parent, lavishing titles and livings on his brood of bastards. Barbara’s children were among his favorites, and raised in a nursery near Barbara’s quarters in the palace. The king visited and played with them daily. Of course Barbara realized this, and made the most of it, flaunting her rampant fertility (she bore the king five children in rapid succession) before the poor queen. How does Barbara’s marriage protect her from scandal? At what point does her husband refuse to remain a party to the countess’s deceit? Married women at court have always been the most convenient royal mistresses. An understanding husband gave the illicit relationship a respectable screen to hide behind, and if any royal bastards were conceived, they could be given the cuckolded husband’s name. A husband also limited a mistress’s ambition; England remembered all too well the trouble caused by the presumptuous Anne Boleyn.

A beautiful woman, Barbara is not so foolish as to believe her looks will endure. How much of her scheming is in service to the future of her children with Charles? Because her own mother had little to give her, Barbara was always acutely conscious of providing for her own children –– or, more correctly, making sure that Charles provided for them. She was also proud of being a Villiers, and believed that the offspring of Villiers and Stuart deserved nothing less than peerages.

Clearly, Barbara’s proximity to the king is infuriating to his new queen. Please contrast Charles’ lush mistress with the barren Iberian queen. Princess or no, Catherine of Braganza never really had a chance against Barbara. By the standards of English beauty at the time, Catherine was small and plain and sallow with bucked teeth, and physically no match for Barbara’s long legs and lush pink-and-white voluptuousness.

Barbara was surprisingly tolerant of Charles’s other lovers, perhaps from recognizing in him her own need for variety. She wasn’t jealous of sharing him sexually in casual liaisons, but she hated seeing her power and influence lessened when his other interests became more serious. Her feuds with the other recognized royal mistresses (including Nell Gwyn and Louise de Kerouelle) were fierce and noisy, and, in the end, finally contributed to her departure from a court she could no longer control. Barbara takes her pleasure with others, if discreetly, including one of the king’s latest infatuations. How does Countess Castlemaine’s blatant sexuality keep the king’s interest as well as deter the lure of other, younger women? From writings of the time, it’s clear that there wasn’t any other woman at court remotely like Barbara. The ideal woman (and wife) was supposed to be modest, quiet, and self-effacing. Barbara’s unbridled enthusiasm for sexual experimentation, joined with her sleepy-eyed beauty, must have made for a potent attraction for a king whose own inclinations were much the same. Although Charles endures an unsuccessful war and increasing shortfalls in his treasury, he continues to entertain Barbara’s demands for jewels and titles. How does this overt generosity with his mistress ultimately affect the king’s popularity? The English people did not share Charles’s affection for Barbara. While she was considered an icon of English beauty, she was also perceived as a dangerous lure to the king, claiming too much of his time and draining away public funds into her own pockets. Her brazen disregard for adultery –– both hers and the king’s –– was cause for public outrage, and when she converted to Catholicism, there was considerable fear that she would lead the king to Rome as well. Barbara Palmer has a long memory, but she eventually exacts revenge on those who have slighted her over the years. Please explain. Barbara was a vengeful woman. She always considered herself a lady of noble blood, a Villiers, and expected to be treated with a certain regard and deference, no matter how scandalous her behavior might be. She never forgot how Lord Clarendon, a faithful supporter of Charles’s since the king’s boyhood, had scorned her during the very early days of her relationship with Charles. For years she plotted and schemed to break Clarendon’s influence over the king, finally succeeding in having the old man banished from court completely. If you wished to prosper at court, it was not wise to have Lady Castlemaine as your enemy. In Royal Harlot Barbara certainly had the intelligence, beauty, and cleverness to prosper in any era. However, I suspect her nature would be an enormous handicap to her in public life, perhaps more so today than in the 1660s. Can you imagine what the tabloids and Fox News would make of her many lovers? Today we seem to expect our celebrities/politicians/leaders to have impossibly spotless reputations, and women are additionally supposed to be perfect wives, mothers, and cookie-bakers as well. The double-standard is alive and well, and I doubt Barbara would be willing (or able) to abide by it, no matter how great the rewards. Are you working on another novel? If so, can you share something about it with us? I’m always working on a novel. My current project is the story of Nell Gwyn, another mistress of Charles II. Though her “job description” might be the same, she’s the antithesis of Barbara: a sprightly, diminutive redhead from the streets and brothels of Covent Garden who rose to prominence as a wildly popular actress in the Restoration theatre. She was quick-witted and generous and blessed with the rare ability both to make Charles laugh, and to win his complete trust. If Barbara was the drama-queen at court, then Nell was the comedienne. Yet even after Nell became the king’s mistress and friends with others in the court, she never forgot her roots among the common people.

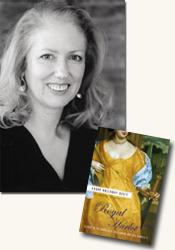

Do you have any words of wisdom for would-be writers? “Words of wisdom”: oh, my! I’ve written more than thirty books over the last seventeen years, but I’m afraid I have even less advice to offer now than I did when I first began. The bottom line with writing is (unfortunately) much like cooking, or ice-skating, or playing a musical instrument: the more you do it, the better you get. You have to figure out what you’re going to say, and then say it, over and over, every day, until you get it right. It’s as easy, and as complicated, as that. A graduate of Brown University, Susan Holloway Scott lives with her family in Pennsylvania. Luan Gaines is a freelance writer and contributing reviewer to curledup.com. Her interview of Susan Holloway Scott was written in conjunction with her review of Royal Harlot: A Novel of the Countess Castlemaine and King Charles II. Luan Gaines/2007.

|

|||||

| fiction · sf/f · comic books · nonfiction · audio newsletter · free book contest · buy books online review index · links · · authors & publishiss reviewers |

|

| site by ELBO Computing Resources, Inc. | |